Antimicrobial Resistance

Antimicrobial Resistance: Understanding AMR, Its Global Impact, and Strategies to Combat It

Understanding Antimicrobials and Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

What Are Antimicrobials?

- Antimicrobials, including antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals, and antiparasitics, are medicines designed to prevent and treat infectious diseases in humans, animals, and plants.

What is Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)?

- Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) arises when bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites no longer respond to antimicrobial medicines.

- As a result, antibiotics and other antimicrobials lose their effectiveness, making infections increasingly difficult or impossible to treat. This leads to greater risks of disease spread, severe illness, disability, and death.

- AMR develops naturally through genetic changes in pathogens over time, but its spread is significantly accelerated by human activities, particularly the misuse and overuse of antimicrobials in treating, preventing, or controlling infections across humans, animals, and plants.

Why is AMR a Global Concern?

- Critical Role of Antimicrobials: Antimicrobials underpin modern medicine, enabling treatments for common infections and life-saving procedures like cancer chemotherapy, caesarean sections, hip replacements, and organ transplants.

- Threat to Global Health and Food Security: Drug-resistant pathogens compromise healthcare systems, reduce agricultural productivity, and threaten food security.

- Economic Impact: AMR drives up healthcare costs through prolonged hospital stays and intensive treatments while reducing productivity in patients, caregivers, and farming industries.

- Global Spread: AMR transcends borders, affecting all nations irrespective of income levels. Key factors include poor sanitation, inadequate infection control, limited access to vaccines and diagnostics, and weak policy enforcement.

- Impact on Vulnerable Populations: Communities in low-resource settings face heightened challenges, disproportionately suffering from the causes and consequences of AMR.

Addressing AMR demands global collaboration, awareness initiatives, enhanced healthcare infrastructure, and the responsible use of antimicrobial medicines in human, animal, and environmental health sectors.

Impacts of AMR on Humans, Animals, Plants, and the Environment

- Animals: Resistant bacteria in terrestrial and aquatic animals lead to increased suffering and losses, impacting the livelihoods of over 1.3 billion people reliant on livestock and 20 million in aquaculture.

- Environment: Antibiotics entering soil and waterways foster resistant bacteria, which can infect humans and animals. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in animal manure can spread to the environment and wildlife.

- Human Health: Misuse of antibiotics in people leads to resistant strains affecting hospitalised patients. Infections like gonorrhoea, cystitis, or those linked to surgeries are becoming harder to treat.

- Food Safety: The link between AMR in animals and human deaths, especially via food-borne infections, remains unclear but is a concern.

To preserve antimicrobials’ efficacy and secure decades of health advancements, controlling AMR is imperative.

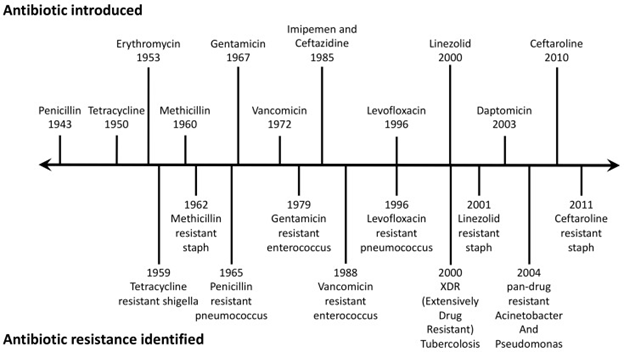

How Do Bacteria Become Resistant to Drugs?

Bacteria develop resistance by evading antibiotic effects through various mechanisms, posing a major ecological and public health challenge. Resistance can occur via:

- Intrinsic Resistance: Some bacteria naturally resist antibiotics by evolving structural changes. For example, penicillin, which targets cell walls, is ineffective against bacteria without cell walls.

- Acquired Resistance: Bacteria gain resistance through mutations or acquiring DNA from resistant bacteria. For instance, Mycobacterium tuberculosis is resistant to rifamycin.

- Genetic Change: DNA mutations in bacteria alter protein production, making antibiotics ineffective. E. coli and Haemophilus influenzae are examples resistant to trimethoprim.

- DNA Transfer: Bacteria share resistance genes through:

- Transformation: Incorporating naked DNA.

- Transduction: DNA transfer via phages.

- Conjugation: Direct bacterial contact.

An example is Staphylococcus aureus resistance to methicillin (MRSA).

Some bacteria, like E. coli and Enterococcus, are resistant to multiple antibiotics, including macrolides, tetracyclines, beta-lactams, and quinolones, posing a severe challenge to global health.

Evidence from UK Prescribing During COVID-19

A recent single-Trust study from England used the WHO AWaRe framework to describe antibiotic use for respiratory tract infections across eight seasonal time-points spanning 2019–2020 (n = 640).

The authors observed a marked rise in “Watch” antibiotics during the COVID-19 period—most notably azithromycin—while “Access” use remained high (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was the most prescribed across both years).

These shifts underscore how pandemic pressures can tilt prescribing towards broader-spectrum agents and reinforce the value of tracking against AWaRe targets (≥60% of use from “Access” antibiotics) within routine stewardship dashboards.

Framed against the wider global AMR burden, such local prescribing surveillance is essential for patient safety and resistance prevention.

Citation: Abdelsalam Elshenawy R, et al., (2023) WHO AWaRe classification for antibiotic stewardship: tackling antimicrobial resistance – a descriptive study from an English NHS Foundation Trust prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Microbiol. 14:1298858. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1298858

Ten Strategies to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

- Public Awareness Campaigns

Educating societies on the dangers of overusing antimicrobials is vital. Well-designed campaigns can reduce unnecessary prescriptions by up to 36% when delivered consistently. - Improved Sanitation and Infection Prevention

Better healthcare systems and living standards cut the demand for antibiotics. For example, improving sanitation in low-income countries could lower antibiotic use for diarrhoea by 60%. - Reduce Agricultural Use and Environmental Impact

Agriculture and aquaculture account for most global antibiotic consumption—over 70% in the U.S. alone. Antibiotics for growth promotion or prevention should be restricted. Notably, up to 90% of antibiotics given to animals are excreted into the environment, fuelling resistance. - Enhanced Surveillance

Monitoring antimicrobial use and resistance is essential. Accurate data on prescribing patterns and resistance mechanisms enable scientists and clinicians to predict threats and shape interventions. - Promote Rapid Diagnostics

Over 67% of antimicrobial therapies are unnecessary due to misdiagnosis. Rapid diagnostic tools can ensure antibiotics are prescribed only when appropriate. - Vaccines and Alternatives

Raising vaccination rates reduces antibiotic demand. Vaccines under development (e.g., against C. difficile and P. aeruginosa) and alternatives such as phage therapy, probiotics, and antibodies also warrant greater investment. - Strengthen the Workforce

Microbiologists, pharmacists, veterinarians, and infection control specialists are central to tackling AMR. Countries must train, recruit, and retain these professionals. - Support Early-Stage Research

Antibiotic R&D is risky and underfunded. Global innovation funds could support high-risk, non-commercial research critical to AMR control. - Incentivise New Antibiotics

Governments and international organisations should provide incentives to pharmaceutical companies to stimulate antibiotic innovation. - Global Cooperation

AMR requires coordinated international action. Embedding One Health principles in G20 and UN agendas can drive meaningful global responses.

By adopting these strategies, we can mitigate AMR’s global impact on health, agriculture, and the environment while ensuring sustainable antimicrobial use across sectors.

What is World Antimicrobial Awareness Week (WAAW)?

- World Antimicrobial Awareness Week (WAAW), celebrated annually from 18-24 November, is a global initiative aimed at increasing awareness of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). It encourages the adoption of best practices among One Health stakeholders to curb the emergence and spread of drug-resistant infections.

- AMR represents a grave threat to public health, impacting human and animal health, food production, and the environment. This year’s theme, “Educate. Advocate. Act now.”, calls on the global community to spread knowledge about AMR, advocate for decisive commitments, and implement concrete actions to address this escalating challenge.

The Role of Pharmacists in Antimicrobial Stewardship

Pharmacists are vital members of the healthcare team and play a key role in promoting antimicrobial stewardship. Their contributions extend across multiple facets of antibiotic management, ensuring responsible use and optimal patient outcomes:

- Medication Dispensing: Pharmacists act as the final checkpoint to verify prescriptions, ensuring antibiotics are dispensed correctly and educating patients on appropriate usage.

- Medication Review: By reviewing medication profiles, pharmacists can identify potential drug interactions, allergies, or duplications, reducing unnecessary antibiotic use.

- Education and Counseling: Pharmacists inform patients about the importance of completing antibiotic courses, potential side effects, and the dangers of non-compliance.

- Collaboration with Healthcare Providers: Pharmacists work closely with physicians and other providers to recommend appropriate antibiotics, alternatives, or narrower-spectrum drugs when needed, contributing to effective antibiotic stewardship.

- Monitoring and Surveillance: Pharmacists track and report antibiotic usage patterns in healthcare settings, identifying trends and opportunities for improving prescribing practices.

Summary

- Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites evolve to resist antimicrobial medicines, rendering treatments ineffective. Pharmacists play an indispensable role in combating AMR by ensuring antibiotics are prescribed, dispensed, and utilised responsibly.

- Through their expertise in medication management, patient education, and collaboration with healthcare professionals, pharmacists are at the forefront of effective antimicrobial stewardship, critical to the global fight against drug-resistant infections.

Log in

Log in Sign up

Sign up